I prefer The Supremes covers of The Beatles’ songs to their originals. It’s a common joke amongst millennials like myself to drag The Beatles for being overrated, but this isn’t that. I actually have an adolescent fondness for The Beatles due to a curly-haired, nice, diabetic straight boy I had a crush on in high school who played “Yesterday” on a guitar in my senior year, when one of the theatre kids organized a “coffee house night.” It’s what passed for chic in the early 2000s at my private, all-male, Catholic school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Then in college during the era where you could see the iTunes libraries of people who were on the same wifi network as you (horrifying technology, worse than racists on Twitter), I pretended to love The Beatles so I could sit next to a taller but crueler straight boy in his dorm while he transferred his Beatles mp3s to my laptop. At some point, after listening to them enough times to keep up conversation, I began to genuinely love The Beatles. In heavy rotation were the dreamy, percussion heavy pop songs from their earlier catalog that didn’t require experience with hallucinogens to be enamored of. Particularly “Michelle,” as written by Paul McCartney with assistance from John Lennon, who told Playboy in 1980 that when it came to their writing partnership, he contributed the “sadness, the discords, a certain bluesy edge” to McCartney’s lightness and optimism. Growing up in a household of Crown Royal, weekend games of Spades between my aunties and my mom, whose turbulent romantic life was set to the warbles of Mary J. Blige and Aaliyah CDs that were played until the acrylic plastic scratched, I was drawn to songs that had a rougher edge, an inspiration rooted in black musical traditions rather than bright, sticky bubblegum whiteness.

Lennon’s inspiration for the “I love you / I love you / I love YOU” bridge in “Michelle” came from listening to Nina Simone’s cover of “I Put A Spell On You” where she put her own emphasis on the “you” in the middle eight of “I Love You.”. That bluesy inflection was Simone’s own. It didn’t exist ten years prior when Screamin’ Jay Hawkins first performed it. And so “Michelle” finally had something that McCartney’s otherwise beautiful lyrics didn’t possess when he first penned the song: soul. I didn’t know any of this my freshman year of college when I listened to “Michelle” on repeat in my muffled Apple headphones after learning that the cruel straight was in fact gay, just not as enamored with me as I was with him and the music he gifted me. I was sad. Heartbroken, I thought I had yet to grasp the concept of love. It was three months before I came out for the first time to the cast and crew of our department’s production of Godspell. Despite its heavy personal associations, I don’t recall crying during any of the times I listened to the song.

I’d grown up with an affinity for The Supremes, through Diana Ross’ status as a legend amongst family elders and ubiquitous classics like “Baby Love” and “Stop! In the Name of Love.” But it wasn’t until I learned what heartbreak was that The Supremes cemented themselves as my never failing misery medication. The first time I heard their 1966 cover of “Michelle,” recorded at The Roostertail in Detroit, Michigan, the tears finally came.

The Supremes began as The Primettes, a group comprised of Diana Ross (who was going by Diane until a clerical error on her birth certificate led to the name Diana), Florence Ballard, Mary Wilson, and Betty McGlown. Barbara Martin replaced McGlown in 1960 and by 1962 Martin herself exited, leaving us with the trio that has been permanently etched in history. The Supremes sung love songs that were written for them, and they also covered love songs written for other people, like those of The Beatles.

Korean American artist Nam June Paik used his work to show how machines could use images from the past—recent or far—to propel us into the future. I like to think of The Supremes as afrofuturism. What else correlates to his quote, “A culture that’s gonna survive is the culture that you can carry around in your head,” besides the black and white recordings of The Supremes performing on televised pop music showcases or late night talk shows in austerely choreographed movements that relied on hand gestures and gentle swaying. Or the records where they sung meticulously crafted love songs from songwriting trio Holland-Dozier-Holland (Swedish pop music manufacturers like Max Martin have got nothing on them, much as I love “...Baby One More Time” and its successors).

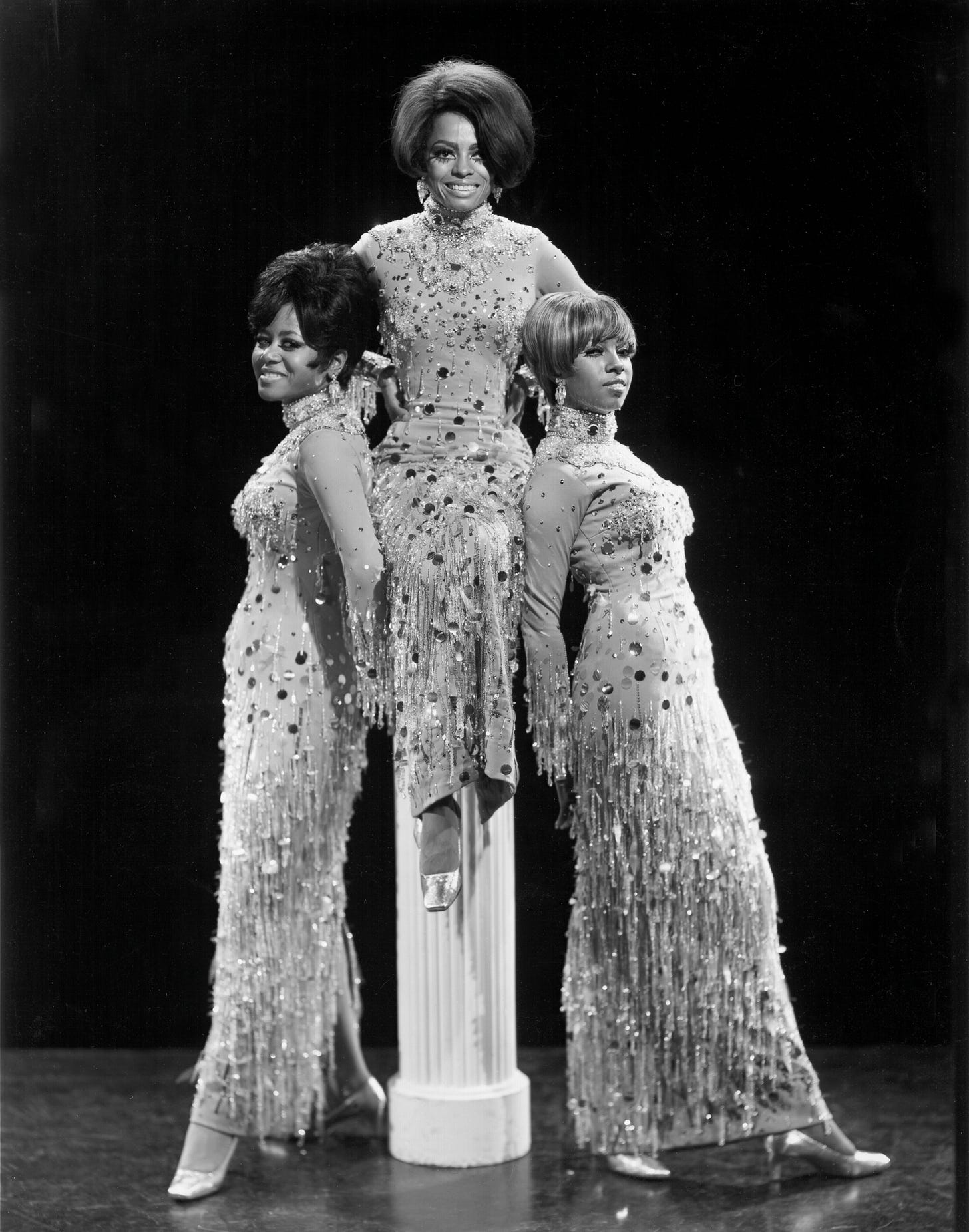

Berry Gordy’s vision of The Supremes, and Motown writ large, was of a future where white people listened to the music of Black people. So Ross and the Supremes were enrolled in Maxine Powell’s Finishing and Modeling School to smooth their “snooty” and unsophisticated rough edges. “I told them they had to be trained to appear in the No. 1 places around the country and even before the Queen of England and the president of the United States,” Powell told Vanity Fair in 2008. Or as Wesley Morris put it in The 1619 Project’s “Why Is Everyone Always Stealing Black Music?”, “Respectability wasn’t a problem with Motown; respectability was its point.” The Supremes produced an image of blackness that was not yet in the public consciousness—an image of Black women in floor-length gowns and evening gloves and perfectly coiffed up-dos and highly styled shortened bobs.

When they sing the love songs of The Beatles, the Supremes take those impersonations of blues and infuse them with the actual lived experience of women who grew up in Detroit’s Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects. They infuse them with a shared heartbreak particular only to Black women in America. And also to queer Black men like myself, who grew up in an environment where emotions and vulnerability were rarely witnessed, and even then, only from the women in my family, and even then only from the women they watched on daytime soap operas who were deemed as “doing the most.” Tenderness amongst men was absent. My father wasn’t in the picture and my great-grandfather was never capable of telling anyone he loved them. His response when my grandmother would tell him, “I love you,” was “Be sweet.” Is it any wonder that once I embraced my queerness and the emancipation that comes with finding your own community, “I love you” became a phrase that flew easily off my tongue? I’ve never experienced what I might call being in love, but my closest friends certainly have heard an emphatic “I love you / I love you / I love you” from me.

As a person who does not find it easy to express their emotions unless it’s 3am and I’m rolling on a packed downtown Los Angeles warehouse dance floor, I tend to use music to hack my own grief and produce tears. Usually, to mixed success. Melancholic songs don’t make me cry when they should. And even though the most saccharine of pop songs have despair nestled in their DNA, too much of that will just rebound against my emotional wall. So what am I to do when I really just want to let the floodgates open? When I want to sink into my bed and let myself become overwhelmed with emotion? I return to the music of The Supremes.

On the album art for 1966’s I Hear a Symphony, Ross, Ballard, and Wilson are dimly lit in soft cyan tones, adorned in immaculate bobs, brightly colored lipstick that lands on the frostier side of a nude lip. Ballard is holding a white dove. They’re frozen in time, and still manage to evoke the image of Blackness unencumbered by the national grief that constantly besieges it. Black people unfortunately understand the science fiction trope of a stranger in a strange land far too well, and you can hear it on “Stranger in Paradise,” which quite literally begins with the lyrics: “Take my hand / I'm a stranger in Paradise / All lost in a wonderland / A stranger in Paradise.”t’s a cover of the song from the 1953 musical Kismet, but here it is imbued with much more longing and sorrow.

I prefer The Supremes covers to their originals.

A haunting melody swells on the night of January 16, 1968 at The Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The Supremes are on stage in sparkly evening gowns adorned with jewels and sleeves. “This is a beautiful number written by some of our favorite composers,” Ross says, highlighting the word “composers” as reverence to Lennon and McCartney as they glide into their own renditions of “Michelle” and “Yesterday.” McCartney’s initial composition of “Michelle” included a jokey imitation of a French man singing. But here, Ross performs the song earnestly. Her hands clenched into fists, telling the story of a man she loves. When she transitions to “Yesterday,” the lyrics are still beautiful, but that lightness and optimism is all gone. All that’s left is the sadness, the discords, that certain bluesy edge Lennon infused into the original. Ross’ rendition breaks my heart. When she sings, “I said something wrong,” she’s fighting back tears, constraining her jaw to maintain composure. My grandmother, who was never told “I love you” by her father, often insisted that I was sent to my high school to “learn something” from the young white boys I attended class with. She said this when we attended school events and she witnessed their respectful composure and polished attire up close. Away from her eyes, they were hurtful with their words and careless with the emotions of others. And yet, to be like them, I had to learn my own austere choreography as a way of distracting or drawing attention to myself.

Last March, my grandmother was diagnosed with cancer. One chilly Los Angeles summer day, overcome with sadness and dread, I climbed into my car and drove up the coast. I drove into the twilight and stared into the sky, contemplating a world where I wouldn’t have to perform the respectability of concealing my volatile emotions. As mania simmered in my skin, “Stranger in Paradise” rattled in my head:

Somewhere in space

I hang suspended

This is so beautiful, thank you for sharing ❣️

that was beautiful! xoxo