I used to blame Pepsi for ruining my life. The sugary cola drink has been a ubiquitous fixture for as long as I can remember. Michael Jackson’s 1985 commercial aired a year before I was born. The Pepsi logo was on display much brighter than Coca-Cola at the corner store near my house. My teen dream Britney Spears kept “The Joy of Pepsi” in my head long after her 2001 Super Bowl commercial. In 2013, I woke up at 5am just to watch Beyoncé debut her own solo Pepsi commercial (she’d done one with Britney, Pink, and Enrique Iglesias years earlier) where she debuted her still-never officially released single “Grown Woman” (No a video does not count).

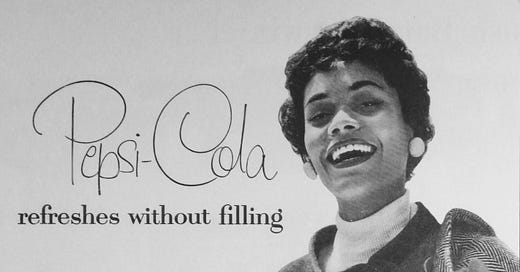

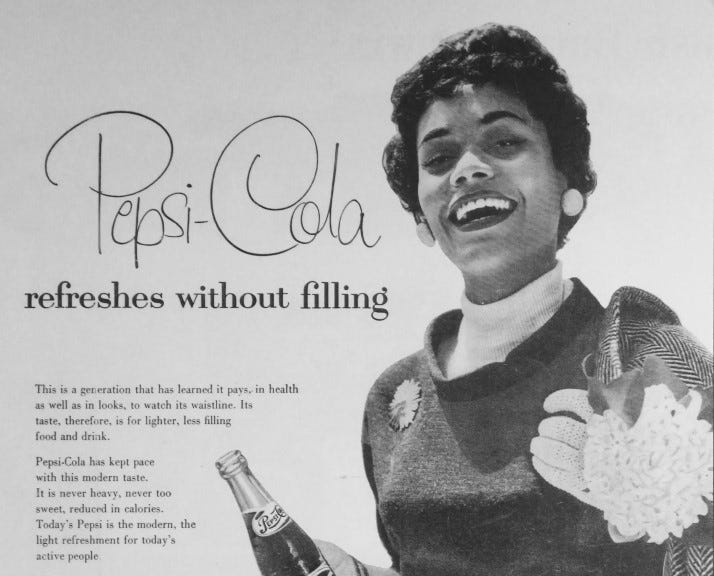

My grandmother grew up in Louisiana during Jim Crow. Until that time, the only images of Black people in advertising consisted of racist slave caricatures like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben. In the 1940s, new Pepsi president Walter Mack realized there was an opportunity to market to Black people in a different way. The cynic in me knows that capitalism will always find a way to exploit Black people, but I want to believe that the reportedly progressive Mack also believed that Pepsi had an opportunity to course correct the offensive caricatures used by Pepsi’s marketing team. He hired Black sales executive Robert Boyd, and Boyd helped usher in an era of an all-Black Pepsi marketing team who weathered the KKK and the racism of their own co-workers in the South as they defied segregation and Jim Crow laws to market directly to Black people. The ads themselves become more reminiscent of the family-centered television sitcoms that would soon dominate the airwaves in the ’50s.

Is it any wonder then that aggressively marketing an aspirational image of Blackness lead to an uptick in sales and would have then led my adolescent grandmother to look at a Pepsi can in a much more favorable light than that other soda that 3D renderings of polar bears drank in commercials? Years later, marketing executives would use images of cool Blackness to market Newport cigarettes to my mother’s generation. There’s certainly no altruism in getting a generation of Black women and men addicted to nicotine. Much like the Pepsi ads, though, I was especially drawn to the Newport ones, and would even rip them out of my mom’s Jet and Ebony magazines while I sweated on her plastic covered couches watching her stories with her.

What you should know about my grandmother is that for most of my developing years, she was ostensibly my mother. I lived with her, and she raised me from adolescence. Another thing you should know is that she was addicted to Pepsi. Yes, Pepsi is addictive. My grandmother’s addiction wasn’t exactly unexpected, given that she doesn’t drink. I, on the other hand, get my doses of dopamine from drugs and alcohol, while she gets hers from that chilled red, white, and blue can that often replaced water during the day and at meals. The colors of that can make Pepsi as American as apple pie, and it’s ironic that it’s at the center of my comedic outing, the same way apple pie exposed Jason Biggs’ character’s sexual urges to his own parents in the movie American Pie just a couple years prior.

When I was in high school, my grandmother got it in her mind that she needed to cut soda out of her diet. She was going to quit her addiction to Pepsi. So what she did was tell me that I could still drink it, but I had to keep it hidden away from her in the house. In retrospect, this probably saddled me with my own fraught relationship with food and dieting (the idea of merely keeping something—anything— “hidden” would be enough to change your own habits.) We were both hiding things then—coming out to my grandmother was more frightening to me than coming out to the mother I had a strained relationship with, and the father I hadn't even seen since I was a child, but it was always something I’d planned to do. Those plans usually involved telling her well after high school. Maybe when I introduced her to a boyfriend, so my sexual orientation seemed normal. I did have one gay example in my family growing up: My uncle Bill and his partner Kevin. But my uncle died in the ’90s, as did many other gay men of his generation, and a living example who should’ve made it easier for me to grow up into a man who was comfortable loving other men publicly was ripped away from me.

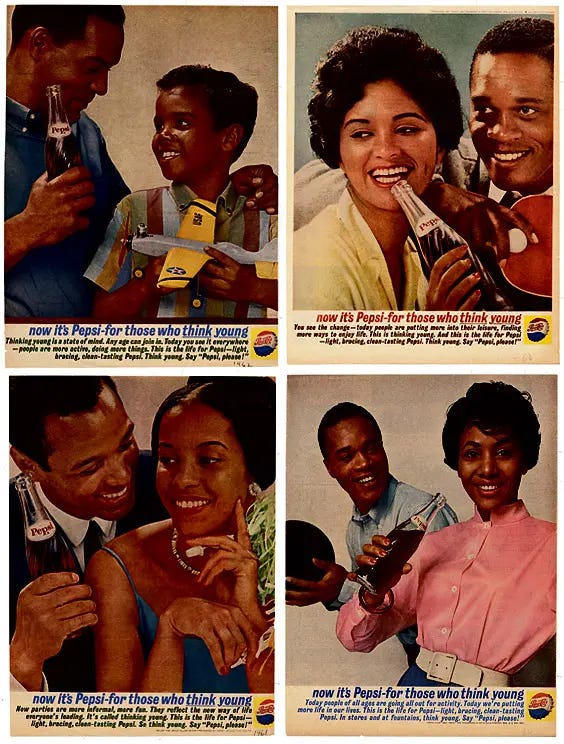

Instead, my queer education came from the internet. During my high school days, internet porn wasn't as available as it is now. Before Twitter, OnlyFans, or even Instagram stories in green close friends bubbles, there were websites like Sean Cody. But my family shared one computer and I’d already been outed as reading x-rated Buffy fanfic where the Slayer fucked her Watcher, Giles—so my solution to not get caught watching porn was to buy a DVD and have it shipped it to my house. It might be hard to remember your teenage decision making skills now, but our logic no—matter how mad hatter—made all the sense in the world to us. The DVD in question was a parody of the Naomi Watts horror film The Ring, from back when she still made good choices about films to star in (what the fuck is a Penguin Bloom?!). It was called The Hole. And if you've ever watched Bravo—and a little show called Million Dollar Listing—you’ll probably recognize former porn star and current Bethenny Frankel reality TV sidekick Fredrik Eklund (who was known as Tag Eriksson then).

I managed to sneak the DVD past my grandmother and into my room without her asking any questions. I'm sure I told her the DVD was Buffy related. I hid it in my room while I was at school, but absent-mindedly, I hid it where I was also hiding… the Pepsi that my grandmother swore she didn't want to drink anymore.

One day I came home from school, and my grandmother was sitting in our living room. She said, "we need to talk." I had no idea what she meant until I dropped my backpack off in my room and found The Hole lying in plain sight on my bed. Could I have been that much of an idiot to just leave it out like that?, then I realized that no, I could not have been.

"You were snooping in my room?" I asked, taking the offense. "I wasn't trying to spy on you," she insisted. "I was looking for a Pepsi and I know you keep them in your room."

Never trust anyone who says they're on a diet.

My grandmother asked if there was anything I wanted to tell her. And here's where I could've come out and ended my high school turmoil of pretending not to be attracted to boys while attending an all-boys school, like some sort of Sisphyean torment. Besides, it was clear she already knew. She had a gay brother, so it didn't take more than reading a couple Nancy Drew books in her youth to figure it out.

But instead, said that "I was going to plant it in someone's locker who I hate." And you know what? She believed me. By that point in high school, I’d already tried to rig a school election… twice… and also once pretended I was mugged to get out of taking a theology exam. I was practically Bart Simpson. So Ira being up to another scam wasn't altogether shocking. "How did you even buy this DVD?" she asked. Which is then when I had to admit I'd used an old credit card of hers I'd found buried in a drawer. That's what actually pissed her off, so she snatched the DVD up and said she was returning it.

The next day, I arrived home from school with the same DVD resting on my bed. "I couldn't return it," she said, appearing in my doorway. "So you can keep it. You know... if you want it." I shrugged. "I guess." Which, I suppose, in my own way, is how I came out to the most important person in my life. I can’t imagine that this particular Black family in the Midwest was what executives imagined their Leave it to Beaver-esque marketing to Black families would lead to, but it did. I guess Pepsi didn’t ruin my life after all.

😂💀 I need a tv series about teenage scammer Ira, please and thank you. Netflix come buy this up!

love the way you write these letters/stories - the “planting of the DVD” moment gave me a visceral response that maybe you’ll include in your own play one day. <3